Anahera Press is honoured to host the article “In Solidarity with the Palestinian people. Memorial Podcast «If I must die»” by Maurizio Montipó Spagnoli paying tribute to the late Palestinian poet Refaat Alareer, featuring a historical background on the context of Palestinian resistance to colonial occupation, and describing the efforts made to create a multilingual podcast of his poem ‘If I must die’. The podcast is dedicated to the Palestinian people who live and resist with dignity, to free themselves from historical conditions of colonial occupation, racial discrimination, apartheid, ethnic cleansing and genocide. So far the project has accrued readings of the poem in 260 languages. This important poem has come to represent both the immense suffering of the people of Gaza, the resistance of oppressed people throughout the world and global demands for a more just world order, freed of the scourges of colonialism and racial discrimination. Please read on if you have an interest in human rights and the poetry of resistance.

In solidarity with the Palestinian People

Memorial Podcast «If I must die»

To the Palestinian people who live and resist with dignity, to free themselves from historical conditions of colonial occupation, racial discrimination, apartheid, ethnic cleansing and genocide.

By Maurizio Montipó Spagnoli[1]

Executive Summary

For more than one century the occupied Palestinian people have been resisting a constant process of belligerent colonisation to defend their right to exist and freely determine their future on their land, Palestine. Where colonial occupation seeks to erase the physical presence, and the discourse of the native people, written and spoken word, storytelling, literature and poetry become an essential form of anticolonial resistance. Written by Refaat Alareer years before his assassination during the genocide in Gaza, the poem “If I must die” is a symbol and a statement of this poetical resistance. Writing and telling its stories, especially in English, the occupied people, the oppressed subject reclaims its right to speak, and breaks in a literary and universal key, the symbolic silence imposed by the occupier. The multilingual podcast of the poem “If I must die” stands as a synthesis of our solidarity and empathy with the Palestinian people and its poets who defend human life and dignity. Reciting Refaat’s poem in as many world languages as possible, 260 to date, participants in this multilingual podcast pay tribute and acknowledge the word and memory of the Palestinian people, and universally condemn the policies and practices of colonial occupation, racial discrimination, apartheid, ethnic cleansing and genocide being inflicted upon them against international law and justice.

Key words: Palestine; poetry; colonial occupation; genocide; resistance.

1. Historical background on Palestinian resistance to occupation

(1) During centuries, Christian regimes and communities across Europe persecuted, segregated and expelled the Jewish communities that were living amongst them, until the horror of the Holocaust. It’s understandable that they should feel guilty and integrate the prevention of any form of antisemitism within their state policies. While it is necessary to draw a clear distinction between Judaism (as a religion) and Zionism (as a colonising political movement), why should the Palestinian people, who have nothing to do with Christian persecutions against Jews and the Holocaust, hand over their land, their resources to a colonizing project intent on expelling them? Europe has a long colonisation history in Palestine: from the Roman Empire, to the Crusades, and the British Colonial Mandate, until the Zionist settler colonization by Israeli settlers of European origin. The root cause of the process of belligerent colonial occupation inflicted upon the Palestinian people during more than one century is the same colonialism which we, Europeans, have invented and practiced on planetary scale, and which remains very much alive in our thought, political, cultural, journalistic and economic practices. Two forms of European colonialism are responsible for the ongoing colonization of Palestine: British colonialism on one side and the Jewish Zionist movement on the other; the former as protector and facilitator, the latter as occupying coloniser. The Palestinian people has been resisting these colonisation processes for over one century (Khalidi, 2020; 2024), in order to defend its inalienable rights and freedom.

(2) Before the end of World war I and the fall of the Ottoman Empire, through the Balfour Declaration (1917), the United Kingdom formally promised to promote the creation of “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. This promise became the official policy of the British colonial mandate in Palestine (1920-1948), facilitating a process of accelerated Jewish colonisation of Palestine, planned in detail by the nationalist Zionist movement with the goal of establishing a Jewish state and funded by the Jewish National Fund, founded in 1901, with the aim of promoting the Jewish settlement in Palestine through the purchase of land, the construction of infrastructure and the establishment of colonial settlements. Between 1917 and 1947 the Jewish population in Palestine grew from 6 to 33% of the total population.

(3) After years of terrorist activity aimed at precipitating the fall of British colonial rule in Palestine (CJIMPE, March 2007; Charif, 2023; Zvaada & Lach, 2022), in 1948, through armed operations of terror and ethnic cleansing, Zionist Jewish militias forced the creation of the state of Israel through the Nakba (the catastrophe), during which they forcibly expelled 750.000 Palestinians, killed other 13.000, rased to the ground and pillaged 531 Palestinian villages, expelled the Palestinian population from 11 cities and took over 78% of Palestine (Pappe, 2006; 2007). In 1967, thanks to a short, illegal “preventive” military aggression against Jordan, Egypt and Syria (Wilde, 2023), “The Six Day War”, Israel occupied the remaining 22% of Palestine (in addition to the Golan Heights in Syria), inflicting a second collective trauma on the Palestinian people, the Naksa (the defeat), forcing into exile another 250.000 Palestinians and submitting those who remained in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza to a colonial belligerent occupation[2] which has been lasting for 58 years.

(4) The Israeli settler colonialism (Tuck e Yang, 2012; Wilson, 2018) keeps occupying and oppressing the totality of the Palestinian people with the goal of expelling and replacing them with Israeli settlers (Albanese, 01 October 2024; 30 June 2025). For decades, Israel has been carrying out a series of coercive and systematic colonization actions in Palestine which have the purpose and result of impairing the fulfillment and enjoyment of the inalienable rights of the Palestinian people: the very right to exist (threatened through genocide and ethnic cleansing), the right to self-determination, the right to return, and the right to reparations for material and moral losses incurred from 1948 onwards. These actions include: ethnic cleansing (S/25274; S/1994/674); forced displacement; racial discrimination; apartheid; constant and systematic wounding and killing of Palestinian civilians, including several, repeated cases of extrajudicial, summary and arbitrary executions of children (Defense for Children Palestine, 2024) by the occupying army and Israeli armed settlers; administrative detentions, arbitrary imprisonment, torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment on a great scale against Palestinian men, women and children; systematic night time searched of Palestinian homes by the occupying army; arbitrary and systematic demolitions, destruction, confiscation or expropriation, of Palestinian homes, land and property (OHCHR, 15 July 2025; Al Jazeera, 3 August 2025); a cruel system of automated surveillance of the occupied population (ICRC, December 2021) in the Palestine Laboratory (Lowenstein, 2023; Al Jazeera, 30 January 2025) through a veritable surveillance industry developed to sustain the occupation, tested on the occupied people and exported; an illegal separation wall more than 700 km long; 849 obstacles to freedom of movement (94 permanent and 153 partial check points, 205 road gates, 101 linear closures – earth walls and trenches -, 180 earth mounds, 116 road blocks) in the West Bank, which subject the economic development, life, well-being, and social relations of the occupied people to the arbitrary power of the military occupation; more than 700.000 settlers illegally settled in the occupied West Bank (out of which, 230.000 in East Jerusalem), distributed in 178 settlements (increased from 128 to 178, +40%, from 2022 to present) which divide and fragment the Palestinian territory and population into a series of separate enclaves unable to communicate with each other; the total blockade of Gaza (lasting for more than 18 years now), the ongoing genocide in Gaza (from 7 October 2023 onwards), and a cynically manufactured famine in Gaza (Al Jazeera, 8 August 2025; ONU 29 July 2025; MEE, 29 May 2025; HRW 19 May 2025).

(5) Israel has been “waging a holocaust in Gaza” whose “true aim” is “the sweeping annihilation of Gaza’s civilian population” and which “cannot be dismissed as the will of the country’s current fascist leaders alone”, because “what we are witnessing is the final stage in the nazification of Israel society” (Noy, 18 September 2025). Israel has been committing four of the five acts that constitute the crime of genocide: a) killing members of the group; b) causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; c) deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; d) imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group (UN, General Assembly, 9 December 1948, art. 2). And it is doing so with “(specific) intent to destroy, in whole or in part, (the Palestinian) … national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such” (Ibid), as proven not only by the pattern of its destructive actions against the totality of the Palestinian people in Gaza, but also by hundreds of inflammatory statements of “direct and public incitement to commit genocide” (Ibid, art. 3, letter c) issued by officials of its government, its army (decision makers) and its parliament (law makers), by combatants and their field commanders, and by public characters capable of influencing public opinion and combat forces on the ground, such as journalists and influencers (Republic of South Africa, 28 December 2023; 29 May 2024; Amnesty International, 2024; Albanese, 1 July 2024; B’TSELEM, July 2025; Palestinian Centre for Human Rights, January 2025; IAGS, 31 August 2025; Law for Palestine, 15 January 2024).

(6) According to Francesca Albanese, UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian Territory occupied since 1967: (1) Genocide, “as the denial of the right of a people to exist and the subsequent attempt or success in annihilating them” is an inherent element of the ideology and processes of settler colonialism that have occurred throughout colonial history (1 July 2024 ).[3] (2) The context and historical process of the Israeli colonial occupation of Palestine is ideologically, politically, and factually compatible and consistent with the current commission of acts of genocide in Gaza (Ibidem).[4] (3) The genocidal intent demonstrated by Israel’s current destructive actions against the entirety of the Occupied Palestinian Territories is contextualized within a decades-long process of territorial expansion and ethnic cleansing aimed at eliminating the Palestinian presence in Palestine (Albanese, 1 October 2024).[5] (4) The economy of occupation, the network of international economic, commercial, and institutional actors that support it, has turned into an economy of genocide. Genocide is economically lucrative for a vast network of international economic powers — arms manufacturers, technology companies, construction companies and businesses, industrial companies in the raw materials extraction and services sectors, banks, pension funds, insurance companies, universities, and charitable associations and foundations — which participate in and promote the two pillars of the colonization process in Palestine: the displacement of the indigenous population and its replacement with settlers. (Albanese, 30 June 2025).[6]

(7) In response to Israel’s aggressive colonisation, which expels, divides and fragments them, the Palestinian people, whether expelled or remaining in their homeland, have developed at least six geographies of their subjectivity: (1) Palestinians living discriminated against in the lands occupied in 1948; (2) Palestinians living in the Palestinian territories occupied in 1967 in East Jerusalem and the West Bank (the former segregated and separated from the latter by the separation wall and an unjust, restrictive and arbitrary system of green cards and permits for access to Israel); (3) Palestinians living in the occupied Palestinian territory of the Gaza Strip (over 50% children, and over 75% refugees), subjected to a total Israeli blockade by land, sea and air, and at least five large-scale military wars of aggression since 2007, in an open-air ghetto or prison where Israel is now subjecting them to a genocide being broadcast live since 7 October 2023; (4) thousands of Palestinians (including women and children) who, as a result of administrative detentions without trial and arbitrary and discriminatory convictions, live in the “Parallel Time” of Israeli prisons, often subjected to torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading conditions of detention; (5) Palestinians in the diaspora, refugees or exiles in Arab countries surrounding Israel or in other Arab countries; (6) Palestinians in the diaspora who are refugees or exiles in the rest of the world.

(8) Furthermore, Palestinian identity shapes itself, across time and space, within a complex network of policies and practices of resistance to occupation, as widespread, dense, systematic and holistic as the policies and practices of colonial oppression. These policies and practices permeate the personal, family and collective dimensions of the experience of every Palestinian, articulating themselves into four fundamental forms of resistance: (1) Individual resistance, articulated by the concepts of “Sumud” (steadfastness) and “Sabr” (patience); (2) Civil resistance (collective networks of belonging, participation and mutual support that provide social, civic, community and educational activities and services essential for the survival and cohesion of Palestinian rural and urban communities located in the territories of 1948, 1967 and in refugee camps in Palestine and neighbouring countries); (3) Popular resistance (political networks of civil disobedience that challenge and resist the occupation by regularly organising protest marches, strikes and other forms of protest that are piece and part of life in the occupied territories); (4) Active armed resistance.

2. In solidarity with the Palestinian people.

Multilingual Podcast “If I must die”

Refaat Alareer (1979-2023)

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze–

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself–

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up

above

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale

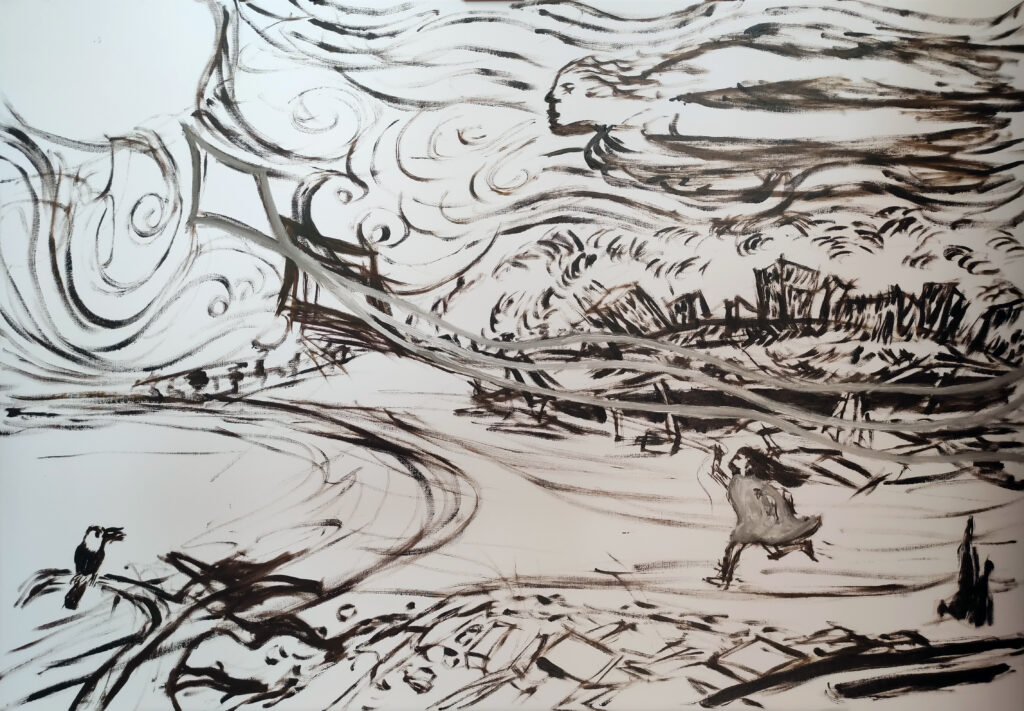

Image: Sketch of the painting ‘If I must die’ by Santi Vela. Courtesy of Santi Vela.

(9) Palestinian writer, poet, professor and activist from the Gaza Strip, English language and literature specialist, Refaat Alareer (1979-2023) was professor of Literature and Creative Writing at the Islamic University of Gaza. He was one of the co-founders of the association We Are Not Numbers, which brings together experienced authors and young writers of the Gaza Strip. His works include two important anthologies promoting the voices and literary narratives of a new generation of Palestinian writers writing in English (the language of the oppressors and their accomplices and allies), to whose education Refaat devoted his entire life: Gaza Writes Back (2014), and Gaza Unsilenced (2015). Refaat was killed by the Israeli bombings along with six members of his family on 6 December 2023 during the genocide in Gaza.

(10) In one of his articles, speaking from the subjective geography of the Gaza ghetto, in whose open-air prison he had lived under siege and segregation for many years, Refaat wrote in 2014:

More than five years ago, during Israel’s 2008–09 twenty-three-day large-scale offensive war on Gaza, Operation Cast Lead, my little daughter, Shymaa, who was only five years old, asked me and my wife a question that still puzzles me (…) “Who created the Jews?” (referring to Israeli settlers (…) Bemused, I offered to tell her a story, and several other stories followed. (…) She must have thought that the merciful and loving God she learns about in her kindergarten, who usually saves the good guys in her mother’s stories, could not be the same God who created those killing machines that for long days and nights brought us nothing but death, chaos, destruction, tears, pain, and fear, causing her and her little brothers to wake up at night and sob hysterically. Her version of God could not be the creator of the same people who caused our windows to shatter and who, two days earlier, shot at her father when I was filling water tanks on the roof of our house during the two-hour ceasefire. Israel’s Operation Cast Lead murdered more than 1,400 Palestinians and injured thousands, most of whom were children, women, and elderly people. Many of the injured are now disabled for life, and many of the martyrs left children and wives orphaned and widowed for life. (…) The war came after a long siege that Israel is still imposing on Gaza, a siege that has left almost all aspects of life paralyzed. Israel targeted infrastructure, schools, universities, factories, houses, and fields. Everyone was a possible target. Every house could be turned into wreckage in a split second. There was no right time or right place in Gaza. (…) It was clear as crystal to Gazans then that Israel was deliberately and systematically targeting life and hope, and that Israel wanted to make sure that after the offensive we had nothing of either to cling to, and that we are silenced forever.” (Alareer 2014, pp. 524-525)

(11) Why then should the occupied, besieged human beings, forced to live under the constant threat of annihilation, condemned to the “duty to die” by violent death, by war, by siege, by genocide, write and tell their stories in English and in universal literary form? Refaat answers us with words that expose and survive to the violence of his murderers.

As a Palestinian, I have been brought up on stories and storytelling. It’s both selfish and treacherous to keep a story to yourself—stories are meant to be told and retold. If I allowed a story to stop, I would be betraying my legacy, my mother, my grandmother, and my homeland. To me, storytelling is one of the ingredients of Palestinian sumud – steadfastness. Stories teach life even if the hero suffers or dies at the end. For Palestinians, stories whet the much-needed talent for life. (…) One day, Mom told us, she was going to school when a shell exploded a few meters away from her. The following day she woke up and went to school like nothing had happened the day before, like she was rejecting the rule of the shells. (In retrospect, I believe that’s why I almost never skipped a class in my life.) But my mother has outlived Israel’s brutal invasion, and so have her stories. During the attack, the more bombs Israel detonated, the more stories I told, and the more I read. Telling stories was my way of resisting. It was all I could do. And it was then that I decided that if I lived I would dedicate much of my life to telling the stories of Palestine and empowering Palestinian narratives and nurturing young voices. (Ibi, pp. 526-527).

(12) From a standpoint of defence of international law, peace and justice, since 2024 DEMOSPAZ, the Institute for Human Rights, Democracy, Culture of Peace and Non-Violence at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM), has been organising a series of initiatives in solidarity with the Palestinian people, with particular focus on their poetic resistance to colonial occupation and genocide.

(13) In the first place, we collected a dossier of 65 poems and writings of Palestinian resistance to the colonial occupation and genocide, translating them into Spanish. This dossier provided us with the script for the collective reading of Palestinian resistance poetry, «The Arc of Refaat and Heba. Let’s Stop the Genocide in Gaza!» (18 April 2024, Madrid) which we have dedicated to the memory of Refaat Alareer (1979-2023), Hiba Abu Nada (1991-2023) and other Palestinian poets brutally murdered during the genocide in Gaza. As of 25 December 2023, Israeli occupation forces’ air, sea and land attacks on Gaza had killed the following Palestinian poets, writers, artists and scholars in Gaza: Heba Abu Nada; Omar Abu Shaweesh; Refaat Alareer; Abdul Karim Hashash; Inas al-Saqa; Jihad Al-Masri; Yusuf Dawas; Shahadah Al-Buhbahan; Nour al-Din Hajjaj; Mustafa Al-Sawwaf; Abdullah Al-Aqad; Said Al-Dahshan; Saleem Al-Naffar.

(14) Reciting Palestinian poems rather than poems about Palestine allowed us to establish a direct dialogue with “(our) brothers and sisters in occupied Palestine”, to “make … the words and resistance of … (their) poets our own”, and to speak to them from the “poetry of freedom that you carry within you and that we will help you achieve” (Preamble to the Act). Poetic resistance articulates the subjectivity, memory and self-determination project of an entire people. To plunge the audience into the terror of genocide, we decided to open this public act with the heart-rending beauty of the poem “The Night of Gaza” by Heba Abu Nada:

Gaza’s night is dark apart from the glow of rockets,

quiet apart from the sound of the bombs,

terrifying apart from the comfort of prayer,

black apart from the light of the martyrs.

Goodnight, Gaza.

(15) We then decided to transform the written word of Palestinian poetry and poetry about Palestine into spoken and recited voice by developing, initially, two audio and vocal resources of awareness, solidarity and condemnation: a podcast of Palestinian poetry of resistance to colonial occupation and genocide (reciting the words of Palestinians under occupation and genocide and speaking to them in and with their words); and a podcast of poetry about and for Palestine, written by non-Palestinian poets (speaking to Palestinians with our words of solidarity and empathy). The episodes of both podcasts respond to five keywords: poetry, Palestine, colonial occupation, genocide and resistance.

(16) Moreover we created a third self-standing multilingual podcast of one single poem of Palestinian resistance: “If I must die” by Refaat Alareer. In this poem the author tragically anticipates his “duty to die”, under the structural violence of the colonial occupation of Palestine. As an occupied Palestinian living in the ghetto of Gaza, under permanent belligerent siege and periodic wars of aggression by the Occupying Power, the poet anticipates his “duty to die” and the brutal circumstances of his assassination along with six members of his family, by Israeli bombardment, on 6 December 2023. The poem “If I must die” became a universal symbol of the global protest and outrage against the genocide in Gaza and the oppression of the Palestinian people because it incarnates the “must die” structural injustice and violence the colonial occupation exerts on the occupied people, forcing them to disappear, by violent death or displacement, and make room for colonial settlers.

(17) Because of its powerful symbolic defence of life and freedom, as inalienable rights of every human being, we have decided to recite this poem not only in Spanish, but to turn it into a multilingual, possibly global memorial, in which poets, writers, activists and citizens from all over the world recite Refaat’s poem in their respective languages, thus paying tribute to the life, dignity and resistance of generations of Palestinians under historical conditions of colonial occupation, racial discrimination, apartheid and genocide, and honouring the memory of the victims and survivors of the genocide against the Palestinian people.

(18) The repeated recitation of the same poem in multiple languages creates a concert of planetary voices and symbolises not only, as the poet asks us, our duty to live, promote and protect life and our shared human condemnation of genocide (the imposition of physical destruction or the duty to die on a human group for the simple fact of existing); but also our duty to remember and preserve the memory, a memorial, an act of recognition, and symbolic justice towards the victims and survivors of the genocide against the Palestinian people.

(19) As of 5 September 2025 the memorial podcast «If I must die» includes translations and recitals of the poem in 227 languages of the world (Table 1), including 9 Pasifika languages (Table 2). Each linguistic contribution is showcased in a monolingual episode and in the collective multilingual episode hosting, one after the other, continent by continent, each and every language contained in the podcast. This initiative is ongoing and keeps collecting new voices and linguistic contributions, with the goal of signaling our shared universal condemnation of this genocide.

(20) Along with the Palestinian American poet Rasha Abdhulladi we ask you, “dear reader, to join (us) in refusing and resisting the genocide of the Palestinian people. Wherever you are, whatever sand you can throw on the gears of genocide, do it now. If it’s a handful, throw it. If it’s a fingernail full, scrape it out and throw. Get in the way however you can. The elimination of the Palestinian people is not inevitable. We can refuse with our every breath and action. We must.”. The poem ‘If I must die’ has become a powerful, universal symbol representing three converging demands for justice: (a) the global protest and outrage against the genocide in Gaza and the oppression of the Palestinian people; (b) the resistance of oppressed peoples and groups across the world; and (c) the demands for a more equitable world order, the end of all forms of colonialism and racial discrimination by an emerging Global South. This podcast humbly recognizes and voices these demands as an underlying subtext of the recited poem.

Table 1. The 260 languages so far included in the multilingual podcast of the poem “If I must die” (Refaat Alareer, 1979-2023).

- Spanish (ES)

- Portoguese (PT)

- Mirandés (PT)

- Galego (ES)

- Asturian Bable (ES)

- Euskera (ES)

- Aragonese (ES)

- Catalan (ES)

- Valencian (ES)

- Mayorcan (ES)

- Maltese (MT)

- Corsican (FR)

- Sardinian (IT)

- English (UK)

- Cymreig-Welsh (UK)

- Gaeilge- Irish Gaelic (IR)

- Gàidhlig- Scottish Gaelic (UK)

- Doric (NE Scots – UK)

- Scots (UK)

- Shaetlan-Shetlandic (UK)

- Manx (IM)

- Brezhoneg/Bretone (FR)

- French (FR)

- Occitan (FR)

- Alpine Occitan (Stura Valley,IT)

- Alpine Occitan (Maira-Varaita Valley,IT)

- Latin (IT)

- Italian (IT)

- Triestin (IT)

- Furlan (IT)

- Rozajanski langäč/Resiano (IT)

- Sudtiroler Dialekt (IT)

- Ladino Fassano (IT)

- Valdaostan Francoprovençal (IT)

- Walser Töitschu

- Koinè Piedmontese (IT)

- Monregalese

- Venesian (IT)

- Ladino Cadorino (IT)

- Ladino Vallada Agordina (IT)

- Fonzasino (IT)

- Trevigiano (IT)

- Opitergino Mottense (TV,IT)

- Paduan (PD, IT)

- Paduan (Cartura, IT)

- Rovigòto (IT)

- Polesano (IT)

- Massese (IT)

- Vicentino (IT)

- Veronese (IT)

- Bresciano (IT)

- Bergamasco (IT)

- Milanés (IT)

- Parmigiano (IT)

- Arsân (RE)

- Arsân (Baiso)

- Arsân (Cavriago)

- Mudnés (IT)

- Bolognese (IT)

- Porrettano (IT)

- Frarés (IT)

- Ravennate (IT)

- Riminese (IT)

- Genovese (IT)

- Poliziano (IT)

- Jesino (IT)

- Ascolano (IT)

- Folignate (IT)

- Perugino (IT)

- Teramano (IT)

- Teatino (IT)

- Pescarese (IT)

- Romanesco (IT)

- Potentino (IT)

- Materano (IT)

- Irsinese (IT)

- Napuletà (IT)

- Duroniese (IT)

- Foggiano (IT)

- Barese (IT)

- Brindisino (IT)

- Tarantino (IT)

- Salentino (IT)

- Roglianese (IT)

- Greek Sila Calabrian (IT)

- Suvaratanu (IT)

- Riggitanu (IT)

- Novarese (IT)

- Galloitalico (Malvagna, ME)

- Catanese (IT)

- Galloitalico (Randazzo, CT)

- Modicano (RG)

- Siracusano (IT)

- Sortinese (SR)

- Niscemese (CL)

- Giurginatano (IT)

- Arbëresh (IT)

- Palermitanu (IT)

- Trapanese (IT)

- German (DE)

- Yiddish (DE)

- Swiss German (CH)

- Ticinese (CH)

- Flemish Dutch

- Frysk/Frisian (NL, DE)

- Danish (DK)

- Faroese (DK)

- Icelandic (IS)

- Norwegian (NO)

- Swedish (SE)

- Meänkieli (SE)

- Finnish (FI)

- Northern Sámi (Sámi)

- Estonian (EE)

- Latvian (LV)

- Lithuanian (LT)

- Polish (PL)

- Belorussian (BY)

- Ukrainian (UA)

- Czech (CZ)

- Slovack (SK)

- Hungarian (HU)

- Slovenian (SI)

- Croat (HR)

- Italian (HR)

- Fiumano (HR)

- Istrosomanzo Dignanese (HR)

- Bosnian (BA)

- Serbian (RS)

- Montenegrin (ME)

- Macedonian (MK)

- Albanian (AL)

- Greek (GR)

- Romenian (RO)

- Bulgarian (BG)

- Turkish (KSV)

- Turkish (TR)

- Arabic (SA)

- Hebrew (IL)

- Arabic (LB)

- Arabic (PL,WB)

- Arabic (PL,Gaza)

- Russian (RU)

- Giorgian (GE)

- Armenian (AM)

- Uzbek (UZ)

- Kyrgyz (KG)

- Mandarin Chinese (CN)

- Taiwanese (TW)

- Janese (JP)

- Korean (KR)

- Filipino – Tagalog (PH)

- Binísayâ-Cebuano (PH)

- Kinaray-a

- Hiligaynon (PH)

- Waray (PH)

- Akeanon (PH)

- Ilokano (PH)

- Maguidanaon (PH)

- Mëranaw/Maranao (PH)

- Bahasa Sinama (PH)

- Bahasa Tausug (PH)

- Blaan (PH)

- Kapampangan (PH)

- Mandaya Kinamayo (PH)

- Bahasa Indonesia (ID)

- Balinese (ID)

- Basa Sunda (ID)

- Bahasa Melayu (MY)

- Sama-Bajau (MY)

- Vietnamese (VN)

- Khmer (KH)

- Thai (TH)

- Burmese (MM)

- Bangla (BD)

- Tibetan (CN)

- Dzongkha (BT)

- Nepalese (NP)

- Sanskrit (IN)

- Hindi (IN)

- Telugu (IN)

- Tamil (IN, LK)

- Kongu Tamil (IN)

- Malayalam (IN)

- Marathi (IN)

- Kannada (IN)

- Gujarati (IN)

- Assamese (IN)

- Urdu (PK,IN)

- Sindhi (IN)

- Punjabi (IN,PK)

- Balochi (IR,AF,PK)

- Pashto (AF,PK)

- Farsi (IR)

- Kurmandji Kurdish (TR,SY,IQ,IR)

- Darija Arabic (MA)

- Arabo Classico (MA)

- Spanish (EH)

- Hassaniya (EH)

- Somali (SO)

- Garre (SO)

- Mauritian Creole (MU)

- Swahili (TZ,KE,MZ,CD,SO,MW,MG,OM)

- Creole (CV)

- Wólof (Wólof, SN, GM)

- Creole (GW)

- Krio – Creole (SL)

- Temne (Temne, SL, GN, GM)

- Igbo (NG)

- Camfranglais (CM)

- Nugunu (Yambasa, CM)

- Ewondo (Beti be Nanga, CM)

- Aghem (CM)

- Runyankole (Nkore, UG,TZ,CD,RW,BI)

- Luganda (Baganda, UG)

- English (TZ)

- Iraqw (TZ)

- Sukuma (TZ)

- Kinyasa/Chinyanja (TZ,MW,MZ)

- Setswana (BW,ZA)

- Kalanga (Ba Kalanga, ZW, BW, ZA)

- English (ZA)

- isiXhosa (Xhosa, ZA)

- Afrikaans (ZA)

- isiZulu (Zulu,ZA)

- Spanish (AR)

- Portoguese (BR)

- Tico Costarricense (CR)

- Spanish (MX)

- Mapudungún (Mapuche, CL, AR)

- Huarpe Millcayac (AR)

- Qomla’aqtac (Qom, AR)

- Quechua (Inca, PE)

- Kichwa (Kichwa Otavalo, EC)

- Shuar Chicham (Shuar, EC)

- Quechua/Runa Shimi (Yanakona,CO)

- Wayuunaiki (Wayuu, CO,VE)

- Papiamento (AW)

- Papiamentu (CW)

- Caribbean Dutch (CW)

- Bribri (Bribri,CR)

- Cabécar (Cabécar,CR)

- Ch’ol (MX)

- Chatino (MX)

- Náhuatl (MX)

- US English (Apache, Navajo)

- US English (Anishinaabe)

- Southern Michif (Métis,CA)

- Kalaallisut/Greenlandic (DK)

- English (AU)

- English (NZ)

- Bola (PG)

- Bebeli (PG)

- Korafe-Mokorua (PG)

- Te reo Maori (Maori, NZ)

- Pohnpeian (FM)

- Hawaiian (US)

- CHamoru (GU)

- Romany (Roma)

- Esperanto

Table 2: Sample of translations and recitals of the poem “If I must die”, by Refaat Alareer (1979-2023) in Pasifika linguistic varieties.

Mehe mate noa ahau

Refaat Alareer (1979-2023)

Te reo Māori (New Zealand)

Translation by Sir Haare Williams

Recital by Kiri Piahana-Wong

Mehe mate noa ahau

Noho ora mai koe

Toku Waitara puakina ake

Oku taonga e hokohokona nei

Rite ki te whiringa muka korowai

He muka harakeke e

He muringa tamaiti no Gaza

E mate kuuare noa nei

Tirotiro kau ana ki a Ranginui

Haere ra e pa kua pungarehuhia

Kei whea ke taku matua ngaro noa –

Kihai rawa mona he Poroporoaki

Kihai rawa mo tona kiri

Kihai rawe mona ake –

Ka kite I te manutukutuku Naana I waihanga

E rere runga makomako

He whakaaro maarohirohi he Anahera kaitiaki

Kai ngakau hokia ake ano ko te aroha

Memene noa ana

Whakapapa-pounamu te moana

Mehe mate noa ahau

Tu ora mai ko te tumanako

Te pono me te aroha

Aata whakairohia

Ma I pahn kamala

Refaat Alareer (1979-2023)

Mahsen en Pohnpei/ Pohnpeian

(Pohnpei, Federated State of Micronesia)

Translation by Simion and Emelihter Kihleng

Recital by Emelihter Kihleng

ma I pahn kamala

ke anahne momour

pwe ken koasoaiiahda ihs ngehi

pwe ken netikihla ahi kepweh kan

pwe ken pwainda kisin mwein likou

oh sahl,

(me pwetepwet oh iki reirei)

pwe serih men nan Gaza

ansou me e kilikileng dahla nan leng

awiawih eh pahpa me lul la nan kisiniei

oh sohte meh men e rahn mwahuihla

pil pein paliwere

de pil pein ih

en kilangada kaid o, nei kaid me ke wiahdahu,

e pipihr nan wehwe

ih medowe nan ansou kis

me tohn leng men mih mwo

wawahdo limpoak

ma I pahn kamala

en miehda koapwoaroapwoar

pwe en mie koasoai pe

Inā Au e Pono e Make

Refaat Alareer (1979-2023)

Ōlelo Hawaiʻi/Hawaiian (Hawaii, USA)

Translation and Recital by Brandy Nālani McDougall

Inā au e pono e make,

pono ʻoe e ola

e haʻi i koʻu moʻolelo

e kūʻai aku i kaʻu mau mea,

e kūʻai mai i ke kapa

a me ke aho,

(e hoʻokeʻokeʻo me ke kakaiāpola loloa)

no laila, he keiki, ma kekahi wahi i Gaza

ʻoiai ʻo ia e hikaʻa lani i ka maka

a e kali nei i kona mākua i haʻalele i ke ahi ʻōlapa

a ʻaʻole ʻo ia i ʻōlelo aloha,

ʻaʻole i kona iʻo,

ʻaʻole i kāna iho—

ʻIke maka ʻo ia i ka lupe, kaʻu lupe āu i hana ai, e hoʻolele nei i luna

a manaʻoiʻo iki i kekahi ʻānela i laila

E hoʻihoʻi nei ai i ke aloha

Inā au e pono e make,

e hoʻolana mai,

e haʻi moʻolelo.

Yanggen Nesisita Para Bai Hu Måtai

Refaat Alareer (1979-2023)

CHamoru (Guåhan/Guam, Mariana Islands)

Translation by Cody Lizama

Recital by Kisha Borja-Quichocho-Calvo

Yanggen nesisita para bai hu måtai,

Nesisita para un kontinuha mulåla’la’

Para un sångan i estoriå-hu

Para un bende todu i guinaha-hu

Para un famåhan pidasun magågu

ya didide’ na hilu

Kosaki un påtgon, giya Gaza

Mientras ha a’atan i matan långet

Ha nanangga si tatå-ña ni ma’pos annai kimason

Ya tåya’ ni hayiyi ha despidi

Ni’ i sensen-ña

Ni guiya mismo

Ha a’atan i papalote, i papalote-ku ni un fa’tinas, na gumugupu hulo’

Ya manhasso’ un råtu na guaha ånghet guihe hulo’

Ni chumuchule’ tatte guinaiya

Yanggen nesisita para bai hu måtai

Puedi u ma chule’ tinanga

Puedi u mulå’la’ i estoriå-hu

If I must die

Refaat Alareer (1979-2023)

Australian English (Australia)

Recital by Thalia Moffat

(AFOPA, Australian Friends of Palestine Association)

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze–

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself–

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up above

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale

If I must die

Refaat Alareer (1979-2023)

New Zealand English (New Zealand)

Recital by Kiri Piahana-Wong

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze–

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself–

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up above

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale

Hini Yau Gamate

Refaat Alareer (1979-2023)

Bola (Papua New Guinea)

Recital by Bernard Kondi

Translation not available

Ewingike Ka kiringe

Refaat Alareer (1979-2023)

Bebeli (Papua New Guinea)

Recital by Maxwellyn Mara

Translation not available

Na ambarena a-mo

Refaat Alareer (1979-2023)

Korafe-Mokorua (Papua New Guinea)

Recital by Julie Mota Kondi

Translation not available

Notes

[1] Maurizio Montipó Spagnoli is a member of DEMOSPAZ, the Human Rights, Democracy, Culture of Peace and Non Violence Institute of the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM) and Researcher with CEIPAZ (Centre For Peace Education and Research, Madrid). He is a Specialist in Institutions and Policies for the Protection of Human Rights (University of Padua), master in Political Science (University of Bologna); Mediation and Conflict Management; Methods and Techniques of Social Research Applied to Social Work (Complutense University of Madrid). He worked in several countries in post-conflict transition as a Human Rights Officer and Adviser with NGOs and IGOs such as the OSCE, European Union and United Nations.

[2] “Territory is considered occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army.

The occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised.” (Convention (IV) respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land and its annex: Regulations concerning the Laws and Customs of War on Land. The Hague, 18 October 1907, Art. 42)

[3] Concerning the relation between genocide and settler colonialism, the Special rapporteur states:

“8. Genocide, as the denial of the right of a people to exist and the subsequent attempt or success in annihilating them, entails various modes of elimination.12 Raphael Lemkin, who coined the term “genocide”, observed that genocide is “a composite of different acts of persecution or destruction”, 13 ranging from physical elimination to the forced “disintegration” of a people’s political and social institutions, culture, language, national sentiments and religion.14 Genocide is a process, not an act.15

9. Genocidal intent and practices are integral to the ideology and processes of settler-colonialism,16 as illustrated by the experience of Native Americans in the United States of America, the First Nations in Australia and the Herero in Namibia. Since it is the aim of settler-colonialism to acquire Indigenous land and resources, the mere existence of Indigenous Peoples poses an existential threat to settler societies.17 The destruction and replacement of Indigenous Peoples therefore become “unavoidable” and take place through different methods depending on the perceived threat to the settler group. Such methods include removal (forcible transfer, ethnic cleansing), movement restrictions (segregation, large-scale carceralization), mass killings (murder, disease, starvation), assimilation (cultural erasure, child removal) and birth prevention.18 Settler-colonialism comprises a dynamic, structural process and a confluence of acts aimed at displacing and eliminating Indigenous groups, of which genocidal annihilation represents the peak.19” [Albanese, Francesca (2024, 01 July), Anatomy of a genocide. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, A/HRC/55/73, paragraphs 8 and 9].

[4] As to the context of the Palestinian genocide, the Special Rapporteur states:

“10. Historical patterns of genocide demonstrate that persecution, discrimination and other preliminary stages prepare the ground for the annihilation stage of genocide.20 In Palestine, displacing and erasing the Indigenous Arab presence has been an inevitable part of the forming of Israel as a “Jewish State”. 21 In 1940, Joseph Weitz, head of the Jewish Colonization Department, stated that there was no room for both peoples together in the country; that the only solution was Palestine without Arabs; and that there was no other way but to transfer all of them: not one village, not one tribe should be left.22

11. Practices leading to the mass ethnic cleansing of the non-Jewish population of Palestine occurred from 1947 to 1949, and again in 1967, when Israel occupied the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip, with mass displacement of hundreds of thousands, killings, the destruction of villages and towns, looting and the denial of the right to return of expelled Palestinians.

12. Since 1967, Israel has advanced its settler-colonial project through military occupation, stripping the Palestinian people of their right to self-determination.23 This has resulted in the segregation and control of Palestinians, including through land confiscation, house demolitions, revoked residencies and deportation.24 Punishing their indigeneity and rejection of colonization, Israel has designated Palestinians as a “security threat” to justify its oppression and “de-civilianization”, namely the denial of their status as protected civilians.25

13. Israel has progressively turned Gaza into a highly controlled enclave.26 Since the 2005 evacuation of Israeli settlers (which the current Prime Minister of Israel, Benjamin Netanyahu, strongly opposed),27 the Israeli settler movement and its leaders have framed Gaza as a territory to be “recolonized” and its population as invaders to be expelled.28 Those unlawful claims are integral to the project of consolidating the “exclusive and unassailable right” of the Jewish people on the land of “Greater Israel”, as reaffirmed by Prime Minister Netanyahu in December 2022.29

14. This is the historical background against which the atrocities in Gaza are unfolding.”

[Albanese, Francesca (2024, 01 July), Anatomy of a genocide. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, A/HRC/55/73, paragraphs 10-14].

[5] As to the observable relation between genocidal intent, territorial expansion and ethnic cleansing in the Gaza genocide, the Special Rapporteur states:

“1. In March 2024, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territory occupied since 1967, Francesca Albanese, concluded that there were reasonable grounds to believe that Israel had committed acts of genocide in Gaza.1 In the present report, the Special Rapporteur expands the analysis of the post-7 October 2023 violence against Gaza, which has spread to the West Bank, including East Jerusalem. She focuses on genocidal intent, contextualising the situation within a decades-long process of territorial expansion and ethnic cleansing aimed at liquidating the Palestinian presence in Palestine. She suggests that genocide should be seen as integral and instrumental to the aim of full Israeli colonization of Palestinian land while removing as many Palestinians as possible. (…)

3. While the scale and nature of the ongoing Israeli assault against the Palestinians vary by area, the totality of the Israeli acts of destruction directed against the totality of the Palestinian people, with the aim of conquering the totality of the land of Palestine, is clearly identifiable. (…)” [Albanese, Francesca (2024, 01 October), Genocide as colonial erasure. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, A/79/384, paragraphs 1 and 3].

[6] With reference to the current transformation from an economy of occupation of Palestine into an economy of genocide, the Special Rapporteur writes:

“1. Colonial endeavours and associated genocides have historically been driven and enabled by the corporate sector,1 Commercial interests have contributed to the dispossession of Indigenous people of their lands2 – a mode of domination known as “colonial racial capitalism”.3 The same is true of Israeli colonization of Palestinian lands,4 its expansion into the occupied Palestinian territory and its institutionalization of a regime of settler-colonial apartheid.5 After denying Palestinian self-determination for decades, Israel is now imperilling the very existence of the Palestinian people in Palestine.

2. The role of corporate entities in sustaining the illegal Israeli occupation and its ongoing genocidal campaign in Gaza is the subject of the present investigative report, which is focused on how corporate interests underpin the Israeli settler-colonial twofold logic of displacement and replacement aimed at dispossessing and erasing Palestinians from their lands. The Special Rapporteur discusses corporate entities in various sectors: arms manufacturers, tech firms, building and construction companies, extractive and service industries, banks, pension funds, insurers, universities and charities. These entities enable the denial of self-determination and other structural violations in the occupied Palestinian territory, including occupation, annexation and crimes of apartheid and genocide, as well as a long list of ancillary crimes and human rights violations, from discrimination, wanton destruction, forced displacement and pillage to extrajudicial killing and starvation.

3. Had proper human rights due diligence been undertaken, corporate entities would have long ago disengaged from Israeli occupation. Instead, post-October 2023, corporate actors have contributed to the acceleration of the displacement-replacement process throughout the military campaign that has pulverized Gaza and displaced the largest number of Palestinians in the West Bank since 1967.6

4. While it is impossible to fully capture the scale and extent of decades of corporate connivance in the exploitation of the occupied Palestinian territory, the present report exposes the integration of the economies of settler-colonial occupation and genocide. In it, the Special Rapporteur calls for accountability for corporate entities and their executives at both the domestic and international levels: commercial endeavours enabling and profiting from the obliteration of innocent people’s lives must cease. Corporate entities must refuse to be complicit in human rights violations and international crimes or be held to account.” [Albanese, Francesca (2025, 30 June), From economy of occupation to economy of genocide. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, A/HRC/59/23, paragraphs 1-4].